Caspar David Friedrich and the University of Greifswald

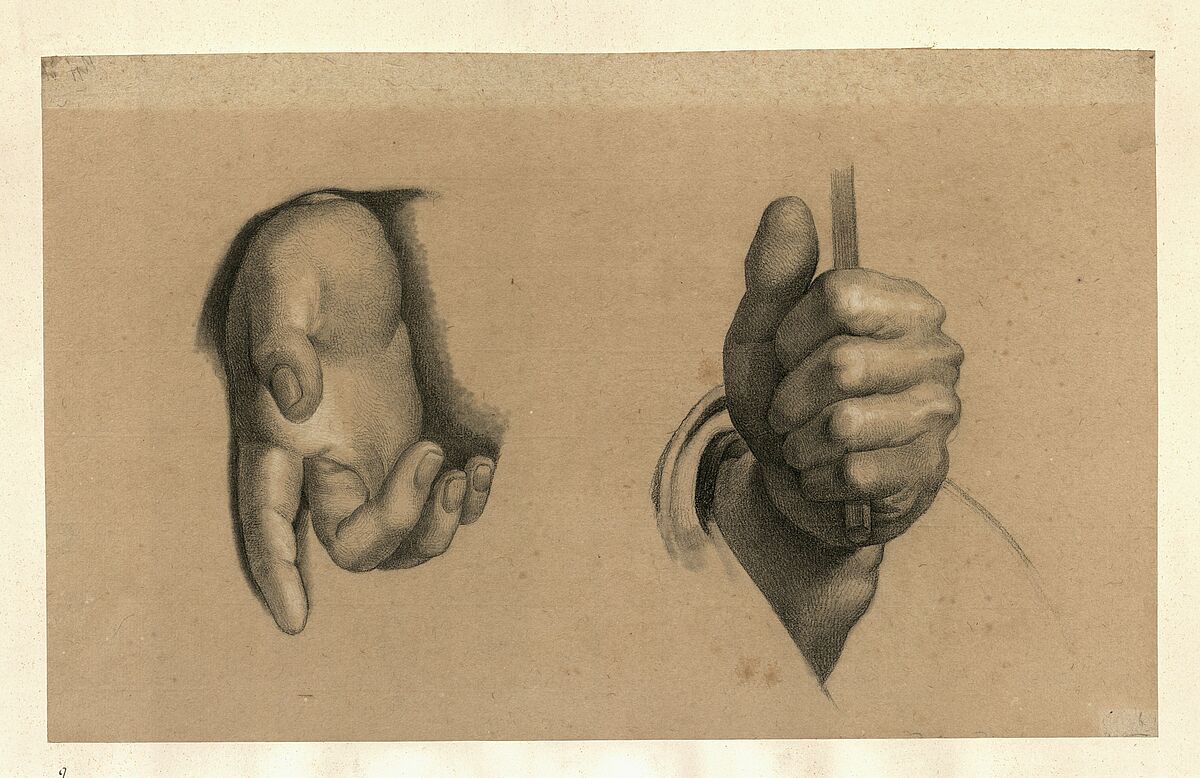

Greifswald is the birthplace of the world-famous painter Caspar David Friedrich. He was born here 250 years ago and grew up with a view of the cathedral, located right next door to his family home, and the Pomeranian sky with its thousand different shades of light. He learned to draw in Greifswald. One of his most prominent teachers was Johann Gottfried Quistorp, University Architect and drawing teacher at the University of Greifswald. Quistorp’s academic drawing atelier that Friedrich once stood in, still exists today. In some respects, it laid the foundation for today’s Caspar David Friedrich Institute.

The town is celebrating the life and work of the painter in 2024 with a programme of events that covers the entire year. You can (re)discover and experience Caspar David Friedrich in more than 160 events being held in Greifswald in 2024.

Augmented Reality-App „CaspAR“

The innovative app ‘CaspAR’ accompanies the fifteen stops of the Caspar David Friedrich Picture Path in Greifswald's town centre and makes it possible for visitors to discover and download fascinating details from the life and work of Caspar David Friedrich onto their tablet or mobile phone. Augmented reality technology lets Friedrich appear as a video hologram on the user’s smartphone, while gamification elements such as chats and quizzes make the app interactive. Two well-known actors, Henner Momann and Julia Maronde, take on the roles of the painter and his wife Caroline and take users on a tour of his life.

Caroline Friedrich knows many interesting details about Friedrich's life and work in Greifswald and vividly remembers which sketches were created during their honeymoon to Greifswald and Rügen. A chat with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe sheds light on Friedrich's professional network, which included a great many contemporary painters. Of course, users can zoom into the paintings on their mobile phone or tablet and study them in detail, and those who are still left questioning can gain deeper insights with the help of video explanations. Even the artist's studio can be explored in 3D!

This app was developed by the Medienzentrum Greifswald e.V. together with the media agency KIDS interactive in Erfurt. Prof. Dr. Roland Rosenstock [de] is the contact at the University.

Lectures and events at the university or with the involvement of the university

Projects in the anniversary year

In keeping with the tradition of close ties between the town and the university, numerous members of the university community will be taking part in the planned celebrations in the anniversary year with contributions in the form of lectures and projects, music, literature and art. The planned projects will be developed by researchers, lecturers and students during the course of the anniversary year and presented here.

Historical Facts

Ten short insights into the history of the University of Greifswald at the times of Caspar David Friedrich, compiled by Dr. Mascha Hansen. With thanks to Dr. Thilo Habel (Kustodie - University Collections), Prof. Dr. Kilian Heck (CDFI), Henriette Maxin (Pomeranian State Museum), Marianne Schumann (Archive) and Thoralf Weiß (Botany) for their expert support in the search for data, facts and photos!

Did Caspar David Friedrich ever study at the University of Greifswald?

No, he didn’t - but he still had close links to the university. This was not only because the university’s buildings shaped the face of the town centre even then, social structures were somewhat different to today. And so, as part of his university tasks as drawing master, the mathematician and painter Johann Gottfied Quistorp (1755-1835), also took on private pupils, including Caspar David Friedrich from 1790 onwards. Quistorp taught his pupils to copy accurately and pay special attention to proportions. (Johannes Grave, Caspar David Friedrich. Munich, London, New York: Prestel. p. 39). His influence on Caspar David Friedrich is still today a subject of debate.

It is conceivable that Caspar David Friedrich also used the university’s Botanical Garden, at that time located behind today’s Main Building, for drawing practice. The garden was managed by Quistorp’s brother, Johann Quistorp, who was more interested in the commercial use of the plants and trees.

From later letters written by Friedrich’s niece, Lotte Sponholz, there is further evidence that a theology student lived in the Friedrich’s house in the Lange Straße, giving home tuition to the children - including the girls. However, we have not been able to find the student she names “Candidat theol Herr Rahbke” in the university’s registers. There is an entry in 1776 for a Joachim Dietrich Röpke from Mecklenburg. At that time, Caspar David would have only been 2 years old, his oldest sister - later Dorothea Sponholz - would have been 10 and might have remembered the young man. It is quite possible that this home tutor was succeeded by others. Whether the sons also visited schools in Greifswald is unknown.

Why did Caspar David Friedrich study in Copenhagen?

The opportunities to study art in Greifswald were, however, very limited; only the paintings and drawings from Quistorp's private collection were available for the usual method of learning to copy works of art by the Old Masters. It was probably also Quistorp who suggested to Friedrich in 1794 that he should continue his training in Copenhagen. Copenhagen was one of Northern Europe’s biggest cultural centres and the art academy didn’t demand any study fees and was considered liberal. It was also no problem to communicate in German there, Friedrich spoke both German and Low German, but there is no evidence to suggest that he spoke Danish. A further reason for choosing the Royal Danish Academy in Copenhagen might have also been the originally strong focus on the training of craftsmen in the fine arts (North, 10). A fellow student was Philipp Otto Runge, who outlined the lessons in letters to his father in Wolgast: Apart from practical exercises, emphasis was placed on geometry in order to learn how to estimate perspectives. A detailed portrayal of the cultural relevance played by Denmark and, more specifically, the Academy of Fine Arts in Friedrich’s time can be found in Michael North’s Caspar David Friedrich: Künstlerischer und kultureller Austausch im Ostseeraum um 1800. Münster/Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2024.

Who was Johann Gottfried Quistorp, Caspar David Friedrich’s drawing teacher?

Johann Gottfried Quistorp (1755-1835), born in Rostock, studied applied mathematics in Greifswald and painting in Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden. He became a drawing teacher at the University of Greifswald in 1788, but also worked as an architect in Greifswald and was appointed University Architect in 1812. Several of the “Quistorp buildings” can still be found in Greifswald’s town centre today, e.g. the “Primary Education Building” in the Steinbeckerstraße 15. The list of his private pupils contains further well-known names: e.g. portrait painter Wilhelm Titel (1784-1862), who himself became a drawing teacher at the University of Greifswald in 1826 and painted several of the portraits of professors still on display today in the Konzilsaal of the University Main Building. Greifswald architect and painter Gottlieb Giese (1787-1838) was also one of Quistorp’s pupils.

The range of Quistorp’s activities was not unusual at that time: professor’s salaries were extremely modest and activities outside of the university were often lucrative. His brother, Johann Quistorp (1758-1834) was Professor of Natural History, Economics and Botany, but also worked as a doctor and obstetrician.

More about the Quistorps can be found in the “Beiträgen zur Genealogie und Geschichte der Quistorps” by Achim von Quistorp here [de] and in Peter Heinke’s Die Quistorps: Portraint einer mecklenburgish-pommerschen Familie, 2008 (p. 25-26).

Did Caspar David Friedrich have any other connections to the University of Greifswald?

Caspar David Friedrich maintained friendly relations with several professors at the university, even long after moving to Dresden. One of these was theologian Ludwig Gotthard Kosegarten (1758-1818), to whom he was presumably introduced by Quistorp whilst Kosegarten was still a pastor on Rügen. Kosegarten was well known for his poems and his sermons in Low German. He also translated the (supposed) bard Ossian from English. In 1808, Kosegarten was appointed Außerordentlicher Professor (Senior Lecturer) of History at the University of Greifswald by the French occupying forces under Napoleon - whom Friedrich vehemently opposed.

A further acquaintance was the law scholar Carl Schildener, who was also a university librarian. He began to collect Friedrich’s drawings early on.

Whilst Friedrich was receiving drawing lessons, Ernst Moritz Arndt studied at the university (1791-1793), the friendship of these two men probably dates back to these years (see Herrmann Zschoche, Caspar David Friedrich: Die Briefe. Hamburg: Conference Point Verlag 2006, p. 86 A detailed account of their friendship can be found in Reinhard Bach’s Caspar David Friedrich und Ernst Moritz Arndt: Identitätssuche im Epochenumbruch. Greifswald: Karl Lappe Verlag, 2023.

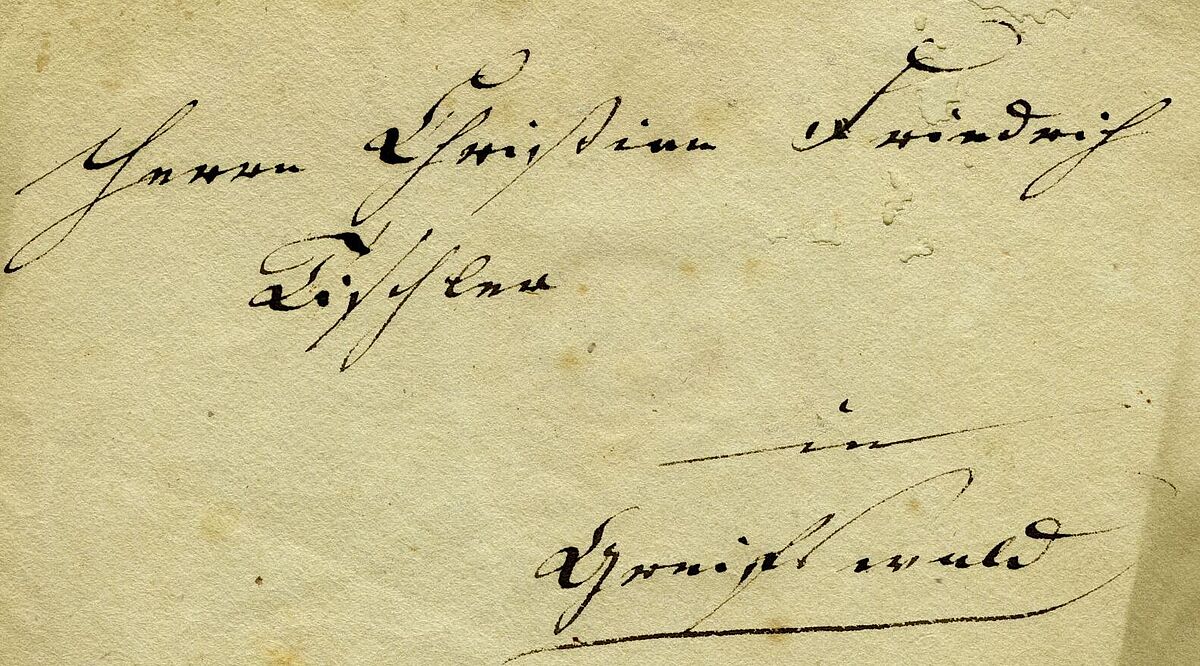

Were there any other connections between the Friedrich family and the University of Greifswald?

It can be assumed that the university required a large number of candles and was therefore a good customer of chandler Adolf Gottlieb Friedrich (1730-1809). Caspar David Friedrich’s brothers took on some of the business of their father, so it can also be assumed that their generation also maintained business relations with the university. There is proof that Christian Friedrich (1779-1843) manufactured specialist furniture for the university: he produced a specimen cabinet and a display case for the natural history collection. The cabinet was delivered with a decorative section that had been designed in a neoromantic style and was not appreciated at the university as the costs were deemed to be too high: “without the superfluous and tasteless decorative sections, [the cabinet] would have been half as expensive” (UAG K562).

Every now and again, Caspar David Friedrich provided sketches for his brother’s furniture, making it possible that the disliked decorative sections were inspired by him. The display case (photo) has remained in possession of the Botanical Garden and is still used for exhibitions today. Further information on the furniture is available from the Head of the Arboretum, Thoralf Weiß (who is compiling a corresponding publication).

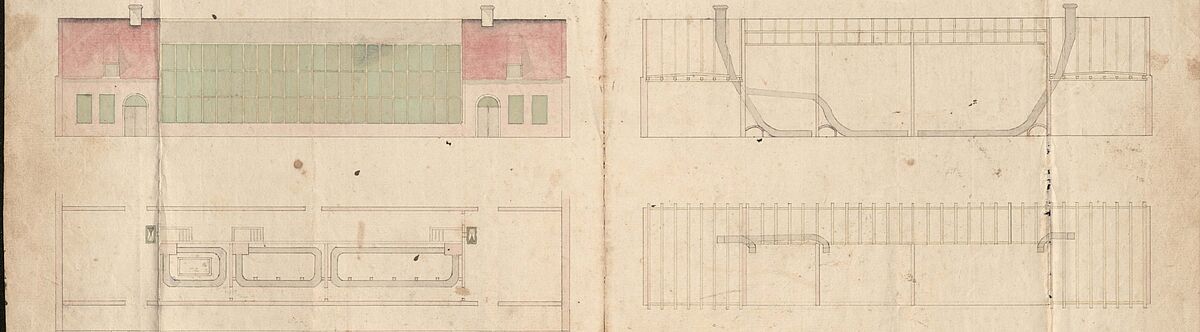

Building materials from the abbey ruins were still being used in the 18th century for the foundation of the greenhouse in the Botanical Garden, which at that time was still located behind the University Main Building (cf. Torsten Rütz and Thoralf Weiß, “Das “grüne” Gedächtnis Greifswalds: Zur Geschichte des Botanischen Gartens und seiner Bauten.” (“The “Green” History of Greifswald: On the History of the Botanical Garden and its Buildings”). Greifswalder Beiträge zur Stadtgeschichte (2017), P.9.

How big was the university at the time of Caspar David Friedrich?

In the Geschichte der Universität Greifswald (“History of the University of Greifswald”) by Johann Gottfried Ludwig Kosegarten, written in 1856/57 (reprinted Scientia Verlag Aalen, 1986), the number of professors under Swedish King Gustav III in 1775 was set at 15, these were complemented by “Adjuncts” and “Privatdocente” as required (p. 315). Between 30 and 40 new students enrolled every year (p. 305) These numbers didn’t change much over the next few decades.

The Eldena Abbey Ruins and the University of Greifswald

The first ties between the Eldena Abbey and the University of Greifswald date back to the 15th century, when several of the monks and abbots were enrolled at the university. During the Reformation, the abbey was dissolved in 1535 and initially served as the ducal seat until it was gifted to the university by Bogislaw XIV in 1634 (see University Chronicle). The buildings had already been damaged in the Thirty Years War, Eldena was further ravaged on several occasions during the 18th century. The former abbey was used as a quarry into the 19th century and it was even at risk of complete demolition around 1827. It might actually have been Caspar David Friedrich who played a decisive role at this point: his drawings of the ruins were well known and Greifswald began its efforts to preserve the ruins. The Prussian King Frederick William III had bought Friedrich’s now famous “Abbey among Oak Trees” in 1810 and also campaigned for the preservation of the ruins on a visit around 1827. However, it still took several years before steps were actually taken towards conserving the Eldena Abbey Ruins.

Further information can be found in: Hans Georg Thümmel, Greifswald – Geschichte und Geschichten. Die Stadt, ihre Kirchen und ihre Universität. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2011 (p. 170).

Were there any female students at the University of Greifswald during Friedrich’s lifetime?

It was not yet possible for women to enroll at German universities during Caspar David Friedrich’s lifetime. The University of Greifswald admitted its first female guest students in 1895 and the first women enrolled for winter semester 1908/09 (University Chronicle).

However, there were exceptional talents every now and again, who – often via family relatives – gained access to university facilities. For example, at the age of only fourteen, Anna Christina Ehrenfried von Balthasar, herself a daughter of a professor, gave a speech in Latin at the opening ceremony for today’s University Main Building on 28 April 1750 with “perfect rhetorical skill”. The chronicler and librarian Johann Carl Dähnert commented: “Maybe this perfect example will also encourage other members of the fair sex to renounce the obstacles that are thought to block their path to the sciences.” He even went one step further and explained that it is “an honour for our academy that a woman publicly declares that she has overcome such doubts and is giving hope through a diligent study of languages and serious sciences” (p.40). She also gave a speech at the opening ceremony of the Academic Library (today’s Aula in the University Main Building) on 14 July 1750 that was even published. Dähnert reports again that “our clever muse” thus delivered proof that “libraries are the safest repositories for true and genuine friendship” and that women were presumably granted access (p. 60). Women were definitely present during the speeches and at the subsequent “entertainments”. On the following day, Anna Christina von Balthasar gained an honorary enrolment and was awarded a “Baccalaurea”.

Hans Georg Thümmel, Greifswald – Geschichte und Geschichten. Die Stadt, ihre Kirchen und ihre Universität. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2011 (p. 135-36).

J. C. Dähnert’s Pommersche Bibliothek (Erster Theil, Greifswald, 1750-1752) [de]

It is known that Johann Gottfried Quistorp, Friedrich’s drawing teacher, held private drawing courses for women. Art academies were also still largely closed to women during Friedrich’s lifetime. However, Caspar David Friedrich was acquainted with several female artists during his time in Dresden: he corresponded with the painter Louise Seidler (1786-1866) and was friends with salonnière Caroline Bardua (1781-1864).

Does the University of Greifswald own drawings or letters by Caspar David Friedrich?

Unfortunately not.

However, the Caspar David Friedrich Institute [de] has a still largely unknown archive on the reception of Caspar David Friedrich’s work with many letters from art dealers (including 20 letters by Wolfgang Gurlitt), digitised images and other documents. They are currently being digitised and processed by Prof. Dr. Kilian Heck as part of a long-term project in collaboration with the CDF collections in Hamburg, Dresden and Greifswald, as well as the University of Jena and TU Berlin.

Furthermore, the university’s Academic Art Collection holds the largest collection of drawings by Wilhelm Titel (1784-1862), a contemporary of Friedrich and further pupil of Johann Gottfried Quistorp.

Have other commemorative anniversaries for Caspar David Friedrich been celebrated previously at the University of Greifswald?

The University organised large festivities for the painter both during the Nazi era on the 100th anniversary of his death (7 May 1940) and during the GDR to celebrate his 200th birthday. Caspar David Friedrich was himself not unpolitical and his paintings bear witness to this: the men often wear traditional German clothes. It seemed obvious to art historians of the Nazi era, especially those at the “Ernst-Moritz-Arndt University of Greifswald” which had been renamed in 1933, that the artist was a pioneer of their ideas. The Rector at that time, Kurt Wilhelm-Kästner, and the art historian Kurt Karl Eberlein published books on Caspar David Friedrich and held an event in the town theatre, to which they (at least) invited high-ranking Nazi leaders. Prof. Dr. Kilian Heck (CDFI) is currently investigating the Nazis’ political appropriation of Caspar David Friedrich, which is the topic of an exhibition arranged together with students and is on display next to Greifswald’s central train station. This was preceded by an NDR documentary [de] on the same topic.

After the war, Caspar David Friedrich was more or less forgotten about; the festivities to mark the 200th anniversary of his birth reintroduced him to public – but also cultural-political – consciousness. For example, in 1974 Greifswald art historian Hannelore Gärtner (1929-2015) was in charge of organising the University’s first interdisciplinary Romantic Conference. The foreword by Deputy Minister of Culture, Werner Rackwitz, in the Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-Universität (Academic Journal of the Ernst-Moritz-Arndt University) from 1976 attests the GDR’s appropriation of the painter: “The events to mark the 200th birthday of Caspar David Friedrich will reaffirm that the working class, the world of socialism, is the true heir to everything immortal in human culture” (p.1). For more on the conference and the contribution made by Hannelore Gärtner, see also Katja Bernhardt, “Kunstwissenschaft versus Kunstgeschichte? Die Geschichte der Kunstgeschichte in der DDR in den 1960er und 1970er Jahren als Forschungsgegenstand” (“Fine Arts versus History of Art? The History of Art History in the GDR during the 1960s and 1970s as a Subject of Research”). Kunsttexte.de [de] (2015), p. 1-19.

This page has the short link: www.uni-greifswald.de/en/cdf250

![CDFI Exhibition [de]](/storages/uni-greifswald/_processed_/b/1/csm_csm_archiv-18_83891144d1_05d7d34d70.jpg)

![Project “Stages of life - The podcast for the Caspar David Friedrich anniversary” [de]](/storages/uni-greifswald/1_Universitaet/1.1_Information/1.1.0_Aktuelles/1.0.0_aktuell/1.0.0.02-caspar-david-friedrich-nur-hochschulkommunikation/csm_Bild-Lebensstufen-Podcast-1200xnn-100dpi_53ce16c9f3.png)